“I lie where I lay this dawn.

“I lie where I lay this dawn.

If I were not here; and I am alien; a bodyless eye; this would never have existence in human perception.

It as none. I do not make myself welcome here. My whole flesh; my whole being; is withdrawn upon nothingness. Not even so much am I here as, last night, in the dialogue of those two creatures of darkness.”

– James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

If I were not here; and I am alien; a bodyless eye; this would never have existence in human perception.

It as none. I do not make myself welcome here. My whole flesh; my whole being; is withdrawn upon nothingness. Not even so much am I here as, last night, in the dialogue of those two creatures of darkness.”

– James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

The title of the installation is a variation on the opening lines of James Agee’s text for the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Agee begins his narration with, “The house had now descended”, “All over Alabama the lamps are out”. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men plays a prominent in the history of photography, often used to illustrate the work of the social documentary photographers working during the Great Depression. The book is atypical of its time, both objectively rich in detail and stylistically subjective in narration, it was a collaboration between the photographer Walker Evans and writer and journalist James Agee.

The book began as a commissioned article for Fortune Magazine on Alabama sharecroppers in 1936. Fortune Magazine was founded by Henry Luce in 1929 at the very start of the Great Depression for a new super-class of the industrial civilization. The audience of the expensively deluxe magazine was educated and urban, as were Agee and Evans who were both living in Manhattan and a world away from the depression era rural south. During the Depression, the magazine became known for its in-depth articles and social conscious.

In researching the article, Agee and Evans travelled to Alabama and spent the summer paying a small rent and living in the family’s house in July of 1936. Although Fortune didn’t publish the article, the piece evolved into a book of Agee’s writings and Evan’s photographs. Unlike social reformers whose photographs and text are intended to effect change in society, the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is a circular and meditative of the homes, environments, of three families of tenant farmers.

Agee begins his narrative with a list of characters, using pseudonyms for the family members rather than their real names. Himself and Evans he describes as “spies, traveling as a journalist and a photographer”. Although he was born in Tennessee, Agee was by that time a New Yorker separated from his subject by class and urbanism. Both Agee and Evans approached their project recognized themselves as outsiders.

“It seems to me curious, not to say obscene and thoroughly terrifying, that it could occur to an association of human beings drawn together through need and chance and for profit into a company, an organ of journalism, to pry intimately into the lives of an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings, and ignorant and helpless rural family, for the purpose of parading the nakedness, disadvantage and humiliation of these lives before another group of human beings, in the name of science, of ‘hones journalism’ (whatever that paradox may mean)”

Agee acknowledged his role as an outsider and reminded the reader of their position as well. “…Who are you who willed these words and study these photographs, and what cause, and by what chance, and for what purpose, and by what right do you qualify to, and what will you do about it…” Agee, Evans, and their audience were all separated from the tenant farmers by time, distance, and culture. Agee is not an omniscient narrator, he is the reader’s surrogate, a first-person pilgrim in a strange land.

The book is an artifact and product of its time. However, it has both effected the evolution of our culture and its themes and concerns of the authors closely parallel our own times. In the 1930s there was a stark cultural divide between Rural and Urban America. As journalists, Agee and Evan’s task was to empathize with and objectively describe the experience of the rural poor to that of the urban elites. There is a fear and distrust described in the book of the tenant farmers for the journalists and the big-city media they work for.

Agee’s own criticisms of printed media was concerned an abdication of the power of words. Spoken by politicians the meaning of words is fluid, absent, or dishonest. Unable to trust the meaning of text Agee’s desired was, “…if I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and excrement…A piece of the body torn out by the roots might be more to the point..” to present the thing itself. In his desire to penetrate the “hidden Truth” of sharecropper life, Agee brings objects into existence through his detailed descriptions. For Evans and Agee, words were failing to convey meaning and an understanding of poor rural life and they veered towards the anthropological contemplation of the things themselves.

Fear is addressed throughout the book. Agee’s own fear is in being the other, and of his role in representing the families, “…not for shame of the people, but in fear and in honor of the house itself…”. Agee describes fears that manifest in sleep, “She is dreaming now, with fear, of a shotgun: George has directed it upon her; and there is no trigger:”. Agee talks of fear in the eyes of the tenant farmers; fear of sadness, fear of more loss, fear of the weather, and fear of the other. And he illustrates the fear of what others think and of what they will do, “… we sat and talked; or rather, you did the talking, and the loudest laughing at your own hyperboles, stripping to the roots of the lips your shattered teeth, and your vermilion gums; and watching me with fear from behind the glittering of laughter in your eyes, a fear that was saying, ‘o lord go please for once, jus for once, don’t let this man laugh at me up his sleeve, or do me any meanness or harm'”

The fears prevalent in the Depression gave rise to the Horror film genre. In early cinema, the post-WWI Depression in Germany gave rise to the earliest horror films such as “The Golem” and “Nosferatu”. The emergence of American horror films after the crash of 1929 made the names of actors like Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff a part of our cultural lexicon.

The xenophobia of the 1930s drove a continual fear of social unrest among the poor. The general anxiety of the period mixed with descriptions and images of poor rural areas seems to have developed in us a fear of that unknown. Hollywood tapped into this and the imagery within horror films seem to reflect the photographs of the era. The decaying house in the forest and hills became an almost universal symbol of something dark and unknown. Horrific newspaper reports of intimidation, cross burning, and lynching illustrate many American’s very realistic fear of monsters in the woods. This cultural imagery coalesced in our consciousness and by the 1950s the decaying rural houses depicted in cinema weren’t worthy of a viewer’s sympathy but established symbols of horror.

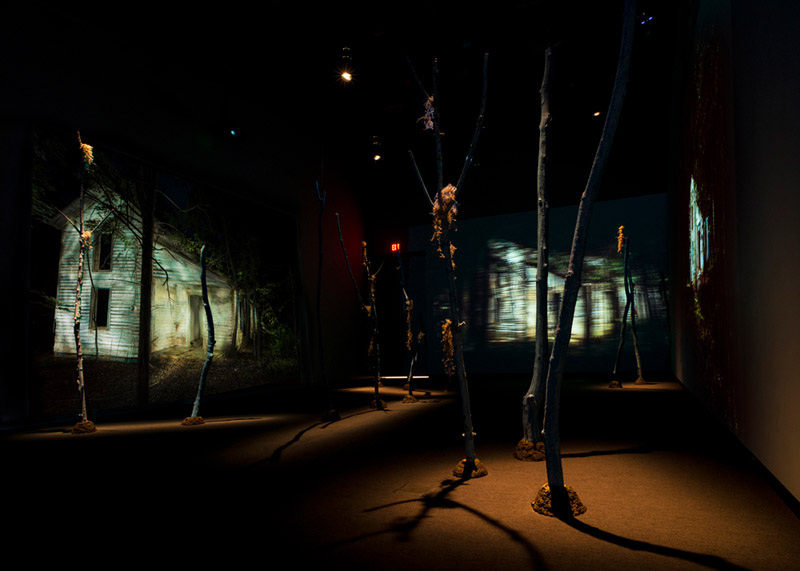

The house that it the subject of the video imagery is deep in the woods of North Carolina, about an hour’s drive from Raleigh. According to local knowledge it was the overseer’s house and one of several structures that remain of a civil war era plantation. The plantation mansion still exists about a half mile away through the woods. Sometime early in the last century the plantation fell and the forest reclaimed the farmland, trapping the house deep in the woods.

The four-channels of video are built of strings of still images of the house painted with light at night. Light painting is an old photographic technique that involves a long exposure and a continuous directional light source. In total darkness, it doesn’t matter if a camera’s shutter is open or closed. Light reflecting off a surface and traveling through the lens produces an exposure and if nothing is lit in front of the camera there can be no image recorded. Far from city lights and under a thick canopy that blocks starlight, a forest in summer provides a very dark space to work with light painting.

A remotely triggered camera on a tripod exposes for 20 seconds while the beam of a flashlight moves over the surface of the house. If the light-painter keeps moving and places themselves between the flashlight and the camera neither they nor the source of the lighting will appear in the image. Without an obvious source for the lighting, the structure seems to glow. Moving the camera to different locations for each shot, I created 30 or more images per scene that could later be edited and used to build strings of hundreds of frames to be assembled and edited into each short scene of the animation. The arrangement of the sequences is loosely based on horror film scores. The effect of the flickering house in the woods is meant to evoke the true tales of spook light sightings and the crafted atmosphere of Hollywood horror films. The house projection is a will-o-wisp seen through the trees, appearing and disappearing just out of reach, until the house sneaks up on the viewer and envelops them.

Without Agee or Evans as surrogates, the viewer is placed at the center of the work. The circular structure of the video piece reflects the circular structure of the narrative in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Audience and environment are a large component of any visual art, and most museum visitors will have more in common with the readers of Fortune than with tenant farmers. The installation is not an attempt at empathy or the understanding, but an illustration of fear and distrust. The flickering and moving will-o-wisp house is cast in the role of “other”, not the audience. Where Agee feared victimizing the house, the house in the gallery is in search of a victim.